|

Had

you lived and died in Britain prior to 1836, your mortal remains

would have found their lasting place in a church graveyard. London's

church graveyards were, however, already full fit to burst and had

been since before the Great Fire in 1666. Sir Christopher Wren,

whilst preparing plans to rebuild the devastated city, called for

new cemeteries to be built outside the perimeter walls but his advice,

like his plans, went largely unheeded.

In

July 1832, after the devastating cholera epidemic of the previous

year and influenced by the commercial success of Britain's first

purpose-built cemetery (St. James's, Liverpool, created in 1825

from a disused stone quarry), the Bill: 'for establishing a General

Cemetery for the Interment of the Dead in the Neighbourhood of the

Metropolis' received Royal Assent, and in its passing privatised

burial.

Between 1833 and 1836, London's first privately-owned cemeteries,

Kensal Green, Norwood, and Highgate, were created. Well-to-do Londoners'

clamoured to purchase grave plots and ensured the new graveyards'

immediate financial success. Within ten years another four commercial

necropoli were raised at Abney Park, Brompton, Nunhead, and Tower

Hamlets. The 'Magnificent Seven', as they became to be known, seem

conservative in their construction when compared to the host of

extravagant applications placed before parliament from other hopeful

joint stock companies. One of the most adventurous schemes, the

'Grand National Cemetery', to have been constructed at either Primrose

Hill or Kidbrooke, was to cover 15O acres. The proposed cemetery

centred around a church modelled on the Parthenon which, in turn,

linked to full-scale facsimiles of the Athenian Acropolis and the

Temple of the Vestal Virgins in the Roman Forum. Burial space was

to be provided on a 1st, 2nd, and 3rd class system; the inner 42

acres for the interment of national heroes, the intermediate ground

for the moderately wealthy, and the outer for the 'humbler class'.

Another

plan, the 'Great Eastern Cemetery', conceived by the social reformer

Edwin Chadwick, was to have been built at Abbey Wood and to have

utilised the adjacent Thames for the transportation of bodies. From

eight London 'reception houses' an average of ninety-six corpses

a day would float down the 'Silent Highway' in specially adapted

steamboats. Chadwick's plan - which also incorporated a glass covered

walkway to protect the mourners from inclement weather, an avenue

of colossal statues, and a chapel surmounted by an enormous stained-glass

dome - was eventually rejected on health grounds when medical authorities

stated that, as twelve-thirteenths of a human body passes into the

air, the 62,000 corpses to be buried in the cemetery would produce

3,038,000 cubic feet of noxious gases. The authorities estimated

that this caustic effluvium would be swept up the river on every

tide, poisoning everything in its path - including the residents

of the City of London.

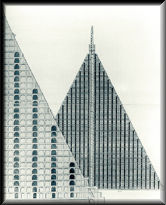

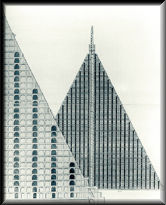

The

most fantastic and extravagant of all, Thomas Willson's 'Pyramid

Cemetery' would, had it been constructed on Primrose Hill, have

dominated London's skyline to this day. The scale of the proposed

pyramid was enormous. Standing higher than St. Paul's Cathedral

and constructed of brick with polished granite facings, it would

have dwarfed the Great Pyramid of Cheops itself. With space for

5,167,104 coffins at a price of £50 per vault, it would also have

proved a moneymaking venture for its investors. Willson, the Gold

Medal winner architect at the Academy School, planned that the building

would be entered by four separate entrances, situated on each of

the pyramid's sides, which would lead to the centre where constructed

around 'a central shaft for ventilation' a small chapel and the

offices of the Superintendent and his minions were situated. Access

to the vaults was to have been along inclined walkways which would

have wound there way to the monolith's apex. The

most fantastic and extravagant of all, Thomas Willson's 'Pyramid

Cemetery' would, had it been constructed on Primrose Hill, have

dominated London's skyline to this day. The scale of the proposed

pyramid was enormous. Standing higher than St. Paul's Cathedral

and constructed of brick with polished granite facings, it would

have dwarfed the Great Pyramid of Cheops itself. With space for

5,167,104 coffins at a price of £50 per vault, it would also have

proved a moneymaking venture for its investors. Willson, the Gold

Medal winner architect at the Academy School, planned that the building

would be entered by four separate entrances, situated on each of

the pyramid's sides, which would lead to the centre where constructed

around 'a central shaft for ventilation' a small chapel and the

offices of the Superintendent and his minions were situated. Access

to the vaults was to have been along inclined walkways which would

have wound there way to the monolith's apex.

Willson wrote:

'...to

toil up its singular passages to the summit, will beguile the

hours of the curious and impress feelings of solemn awe and admiration

upon every beholder'.

Willson's

grand scheme was eventually rejected as being too adventurous.

|